Fracking our Farms: A Tale of Five Farming Families

Fracking our Farms: A Tale of Five Farming Families

-

By Alexis Baden-Mayer

February 20, 2013

Author’s note: On Sunday, Feb. 17, I marched with the OCA at the Forward on Climate rally in Washington, D.C. At one point, our banner, “Cook Organic Not the Planet,” caught the eye of a dairy farmer. He approached. I handed him a flyer and launched into my pitch about how organic agriculture has the power to bring dangerous carbon dioxide levels back down to the safe level of 350 parts-per-million. He nodded politely, then stopped me short with this “If they frack all the farms, there isn’t going to be any organic.” Back home, I sat down at my computer to research farms and fracking. I learned that there’s a growing movement of farmers around the country who are fighting fracking. And I found some stories that should give all of us pause.

Their names are Carol, Steve & Jackie, Susan, Marilyn & Robert, and Christine. They share a bond. Two bonds, actually: They all own, or owned, farms. And those farms, along with their own health and the health of their farm animals, have all been ruined by fracking.

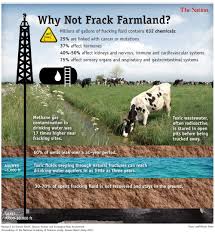

More than 600,000 fracking wells and waste injection sites have popped up across the country, according to ProPublica. The oil and gas industry, along with federal regulators, would have you believe that injecting trillions of gallons of toxic liquid deep into the earth is harmless.

But tell that to Jacki Schilke of North Dakota, who lost two dogs, five cows, chickens – and her health – after 32 oil and gas wells sprouted up within three miles of her ranch. Or Christine Moore, a horse rescuer in Ohio, who sold her farm after a well went up five miles from her farm, creating an oily film on her water and making her too sick to care for her horses.

With hundreds of thousands of fracking wells and waste injection sites in the U.S., it’s likely that our food supply already contains water, plants and animals (meat) contaminated with fracking chemicals. While we hear a lot about drinking water contamination, including people’s water catching on fire straight out of the faucet, that shouldn’t be our only concern. Contaminated crops and farm animals raised for food are also possible avenues for exposing humans to fracking chemicals.

Of course, not all farm animals are destined for the food chain. Those unfortunate enough to live near fracking wells can tell us a lot about the potential danger from fracking chemicals to our own health. Farm animals have the same susceptibility to disease that we have, but because they are exposed continually to air, soil and groundwater, and have more frequent reproductive cycles, they exhibit diseases more quickly, presaging human health problems. A study involving interviews with animal owners who live near gas drilling operations revealed frequent deaths. Animals that survived exhibited health problems including infertility, birth defects and worsening reproductive health in successive breeding seasons. Some animals developed unusual neurological conditions, anorexia, and liver or kidney disease.

What causes those health problems? Among the hundreds of toxic chemicals used in fracking are arsenic, benzene, ethylene glycol (antifreeze), formaldehyde, lead, toluene, Uranium-238. and Radium-226. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ list of common health problems from exposure to fracking chemicals includes autism, asthma, cancer, heart disease, kidney failure, infertility, birth defects, allergies, endocrine diseases and immune system disorders.

Farmers fighting back

Thankfully, many farmers are fighting back. Here are the tales of five farmers on the front lines of the fracking fight who are heroically sharing their tragic stories with the world in an attempt to expose the lie that natural gas is “cleaner power.”

Carol French, dairy farmer and cofounder of Pennsylvania Landowners Group for Awareness and Solutions (PLGAS). Carol’s Bradford County farm is surrounded by nine gas wells. Earlier this month, Carol posted to the Fracking Hell Facebook group that she had just lost three calves in nine days. “I have heard from other farmers with ‘changed’ water having similar problems,” she wrote. At the September 2012, Shale Gas Outrage protest in Philadelphia, Carol told the crowd how, two weeks after their water changed, her daughter developed a fever and diarrhea that turned to blood. She lost ten pounds in seven days. Watch Carol’s speech.

Steve and Jacki Schilke North Dakota ranchers. There are 32 oil and gas wells within three miles of Steve and Jacki’s 160-acre ranch. Jacki blames the wells for the loss of two dogs, five cows and a number of chickens, as well as the decline of her own health. Her symptoms began a few days after the wells were fracked, when a burning feeling in her lungs sent her to the emergency room. After that, whenever she went outside she became lightheaded, dizzy and had trouble breathing. At times, the otherwise fit 53-year-old, can’t walk without a cane, drive or breathe easily. She warns landowners against making deals with frackers: “They're here to rape this land, make as much money as they can and get the hell out of here. They could give a crap less what they are doing here. They will come on your property look you straight in the eye and lie to you.” Watch Jacki talk about her experience.

Susan Wallace-Babb, Colorado rancher. One day in 2005, Susan Wallace-Babb went out into a neighbor's field near her ranch in Western Colorado to close an irrigation ditch. She stepped out of her truck, took a deep breath and collapsed, unconscious. Later, after Susan came to and sought answers, a sheriff's deputy told her that a tank full of natural gas condensate less than a half mile away had overflowed into another tank. The fumes must have drifted toward the field where she was working, the deputy said. The next morning Susan was so sick she could barely move. She vomited uncontrollably and suffered explosive diarrhea. A searing pain shot up her thigh. Within days she developed burning rashes that covered her exposed skin, then lesions. Anytime she went outdoors her symptoms worsened. In 2006, she moved to Winnsboro, Texas, a small town two hours east of Dallas. In 2007, Susan testified in Congressional hearings on the health impacts of fracking. For three years her symptoms gradually improved, until she could work in her garden and go about her normal daily routine. Then, in early 2010, Exxon launched a project in an old oil field 14 miles away and began fracking wells to get them to produce more oil. Within months, Susan’s symptoms returned. Watch Susan’s testimony at the Congressional hearings.

Marilyn and Robert Hunt, West Virginia organic farmers. The Hunts own a 70-acre organic farm in Wetzel County, where they raise goats, chickens and cattle. When the landman from Chesapeake Energy approached the Hunts to lease their mineral rights, Marilyn did some research then turned down the offer. But that didn’t stop Chesapeake from, as she told ShaleReporter.com, “stealing gas from both sides of our property.” In 2010, Chesapeake received a permit for land disposal near her property and dumped waste on her land. “The water got little white flecks in it, and we started to get sick,” Marilyn said. “We lost a whole lot of baby goats that got gastrointestinal disorders from drinking the water.” Some of the baby chicks her daughter was raising died of nervous system failure, and the ones that survived were deformed. Interestingly, though, the cattle that drink from the spring water on the highest point of her property were spared any adverse impact, leading Marilyn to believe it was the water contaminated by the fracking waste that caused the illnesses.

Christine Moore, Ohio horse rescuer. Christine Moore and her family lived a dream life rescuing horses deep inside Ohio’s Amish country. When a well was fracked five miles from her house in January 2012, Christine went door to door, begging her neighbors not to lease their land for fracking. But most of the town, many Amish and Mennonite, didn’t listen. Two months after the well near her home was fracked, the water went bad. An oily film formed across the surface of the water in her horses’ bowls. The water inside her home, pumped from her well and filtered through a softener, began giving her severe stomachaches. She sent her horses to a no-kill shelter in upstate Ohio and, in July, sold the property to her neighbor who, according to Tuscarawas County records, has oil and gas exploration leases on multiple properties. Watch Christine describe how fracking destroyed her horse farm.

Stop the Frack Attack!

Want to join with farmers fighting fracking? Join the OCA on Mar. 2 – 4 in Dallas, Texas, for the National Summit to Stop the Frack Attack!

The summit is expected to draw hundreds of people who will share stories and learn how to become better spokespeople, learn about clean energy alternatives, celebrate fracking victories, and strengthen this national movement. There will also be a rally in Austin on Mar. 4 to welcome the Texas state government back to work. And to remind them they work for the people, not the oil and gas industry.

If you can’t make it to the summit or rally, please consider donating to a scholarship fund so others can attend.

Alexis Baden-Mayer is political director of the Organic Consumers Association.

Source: http://www.organicconsumers.org/articles/article_27073.cfm

A

new report published Monday by the United Nations Environment Program

(UNEP) implicates the global industrial farming system in the disastrous

impacts that fertilizer abuse and waste are having on our natural

world.

A

new report published Monday by the United Nations Environment Program

(UNEP) implicates the global industrial farming system in the disastrous

impacts that fertilizer abuse and waste are having on our natural

world.